Review Whose judgments are least likely to be influenced by automatic stereotype activation?

Mẹo Hướng dẫn Whose judgments are least likely to be influenced by automatic stereotype activation? 2022

Hoàng Quang Hưng đang tìm kiếm từ khóa Whose judgments are least likely to be influenced by automatic stereotype activation? được Update vào lúc : 2022-11-12 03:40:08 . Với phương châm chia sẻ Bí kíp về trong nội dung bài viết một cách Chi Tiết 2022. Nếu sau khi tham khảo tài liệu vẫn ko hiểu thì hoàn toàn có thể lại Comment ở cuối bài để Ad lý giải và hướng dẫn lại nha.- Journal List HHS Author Manuscripts PMC2852264

Pers Soc Psychol Bull. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 Apr 9.

Nội dung chính Show- AFFECT & STEREOTYPE ACTIVATIONTHE PRESENT RESEARCHExperiment 1ParticipantsManipulation

ChecksStereotype ActivationExperiment 2ParticipantsMood manipulation

checkStereotype activationExperiment 3ParticipantsMood Manipulation CheckStereotype activationExperiment 4ParticipantsMood-manipulation checkError ratesPDP analysesGeneral

DiscussionAcknowledgmentsContributor InformationIn what ways do stereotypes influence people's judgments?What are the factors that influence stereotypes?What is stereotyping Judgement?How are stereotypes activated?

Published in final edited form as:

PMCID: PMC2852264

NIHMSID: NIHMS178178

Abstract

Extant research demonstrates that positive affect, compared to negative affect, increases stereotyping. In four experiments we explore whether the link between affect and stereotyping depends, critically, on the relative accessibility of stereotype-relevant thoughts and response tendencies. As well as manipulating mood, we measured or manipulated the accessibility of egalitarian response tendencies (Experiments 1-2) and counter-stereotypic thoughts (Experiments 3-4). In the absence of such response tendencies and thoughts, people in positive moods displayed greater stereotype activation —consistent with past research. By contrast, in the presence of accessible egalitarian response tendencies or counter-stereotypic thoughts, people in positive moods exhibited less stereotype activation than those in negative moods.

Keywords: mood, stereotyping, affect as information

People are cognitive gamblers (Miller, Galanter, & Pribram, 1960; Moskowitz, 2005). In order to successfully negotiate the complexities of daily life, people regularly deploy a variety of cognitive short-cuts, including scripts, schemas, judgmental heuristics and stereotypes (Bruner, 1957; Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2000). This tendency is so entrenched that it typically unfolds automatically, exerting a nearly invisible impact on thought and behavior (Bargh, 1999). Stereotypes, for example, are commonly thought to be activated whenever one encounters or merely considers members of stereotyped groups. Given the wide-variety of social categories that elicit automatic stereotype activation, including race (Devine, 1989), gender (Banaji & Hardin, 1996; Blair & Banaji, 1996), and age (Hense, Penner, & Nelson, 1995), this propensity is often considered to be an unavoidable consequence of our cognitive architecture.

Recent research, however, reveals that automatic stereotype activation can be short-circuited by a variety of motivational forces (Blair, 2002; Kunda & Spencer, 2003). Both chronic and temporary motivational states can curb the activation of stereotypes. People motivated by a chronic goal to be egalitarian, for example, display less gender-stereotype activation than people not so motivated (Moskowitz, Gollwitzer, Wasel, & Schall, 1999). Individuals internally motivated to control prejudiced reactions (Devine, Plant, Amodio, & Harmon-Jones, & Vance 2002) and those who disavow prejudiced attitudes (Lepore & Brown, 1997) display less stereotype activation than individuals motivated by external reasons to control prejudiced reactions and those who endorse prejudicial attitudes, respectively. Finally, stereotype activation is undermined or even inhibited when the stereotype conflicts with short-term self-enhancement goals (e.g., L. Sinclair & Kunda, 1999).

Contextual factors also regulate stereotype activation (Blair, 2002). When people are exposed to counter-stereotypic exemplars (e.g., strong female leaders), for example, they display less stereotype activation than those exposed to neutral stimuli (e.g., flowers), because exposure to such exemplars makes counter-stereotypic thoughts more accessible than stereotypical ones (Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004). Similar reductions in stereotype activation are found when people entertain counter-stereotypic expectations about gender or merely imagine counter-stereotypic exemplars (Blair & Banaji, 1996; Blair, Ma, & Lenton, 2001). Finally, people who form implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1999) to think counter-stereotypic thoughts (i.e., safe) when they encounter African Americans display less stereotype activation than those who do not form such intentions (Stewart & Payne, 2008). In summary, although stereotypes are often automatically activated when people encounter, or merely consider, members of stereotyped groups, stereotype activation can be curbed, or even reversed, by an array of motivational and contextual factors.

AFFECT & STEREOTYPE ACTIVATION

Although the (frequent) experience of positive affect, compared to negative affect, has many advantages, including increased creativity and more success in myriad life domains (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005), it also comes with a number of disadvantages. Chief among these is that positive affect, as compared to negative affect, seems to elevate people’s reliance on a range of cognitive short-cuts, including scripts, schemas, judgmental heuristics, and—most germane to the present research—stereotypes (for a review, see Schwarz & Clore, 2007). When judging a defendant’s guilt, for example, people in positive moods rely more on stereotypes than those in negative moods and neutral moods (Bodenhausen, Kramer, & Susser, 1994; Krauth-Gruber & Ric, 2000). People in positive moods are also more likely than those in negative moods to make stereotype-tinged evaluations of individual group members and groups as a whole (Lambert et al., 1997). Finally, affect may influence stereotyping the activation stage, as well as the application stage; recent research demonstrates that people in positive moods display greater activation of race and gender stereotypes than those in negative moods (Huntsinger, Sinclair, & Clore, 2008; Park & Banaji, 2000).

Explanations for the connection between affect and stereotyping have included the possibility that positive affect reduces cognitive capacity (e.g., Mackie & Worth, 1991) or processing motivation (e.g., Schwarz, 1990), thereby increasing reliance on stereotypes as cognitive shortcuts. From a cognitive capacity account, positive moods activate more mental content than negative moods, which reduces the ability of people in positive moods to deploy cognitive resources to meet task demands (e.g., Mackie & Worth, 1991). The motivational perspective holds that people in positive moods put forth little cognitive effort because they either want to preserve their positive mood or because they see little grounds to do so (e.g., Schwarz, 1990; Petty & Wegener, 2001).

In recent years, these perspectives have been challenged on a number of grounds. Incompatible with a cognitive capacity account, even positive mood inductions that are not likely to elicit much cognitive content (e.g., posing a happy facial expression) produce increased reliance on stereotypes (Bodenhausen et al., 1994). Further, when information conflicts with the implication of an activated stereotype, people in positive moods readily discard the stereotype and, instead, focus on individuating information—a result not easy to explain via the idea that positive mood reduces processing motivation (Bless, Schwarz, & Kemmelmeier, 1996). In sum, individuals in positive moods appear to have both the capacity and the motivation to apply whatever cognitive effort situations demand.

As a result, rather than attributing the link between affect and stereotyping to capacity or motivational limits, most explanations of the relation between affect and stereotyping now hinge on the idea that affect signals the state of the environment, which, in turn, regulates reliance on general knowledge structures (i.e., stereotypes). According to these perspectives, positive affect signals a benign environment, which triggers reliance on pre-existing general knowledge structures such as stereotypes, whereas negative affect signals a problematic environment, which deters reliance on such structures (Bless, 2001; Bless, Clore et al., 1996; Bless & Fiedler, 2006; Schwarz, 2001).

THE PRESENT RESEARCH

In the present research, we asked whether and how motivational and contextual factors known to regulate stereotype activation would moderate the link between affect and stereotyping. We saw two distinct possibilities. According to a strict reading of the predominate state-of-the-environment models, affect is directly linked to reliance on stereotypes: positive affect only triggers reliance on pre-existing general knowledge structures such as stereotypes and negative affect only triggers avoidance of stereotypes or other preexisting general knowledge structures. In light of this direct, exclusive connection, then, people in positive moods should display greater stereotype activation than those in negative moods, regardless of the presence or absence of egalitarian response tendencies, exposure to counter-stereotypic exemplars and so forth.

According to a less strict reading of these state-of-the-environment models, affect regulates the use of any accessible thoughts and response tendencies rather than just pre-existing general knowledge structures. From this less strict perspective, positive affect signals that any accessible cognitions and response tendencies are valuable whereas negative affect signals they are not valuable, which leads people in positive moods to embrace, and those in negative moods to reject, such mental content (Brinol, Petty & Barden, 2007; Clore & Huntsinger, in press; Fishbach & Labroo, 2007). Evidence consistent with this idea comes from research on affective influences on self-validation processes (e.g., Brinol et al., 2007), goal pursuit (Fishbach & Labroo, 2007; Huntsinger & Sinclair, 2008), implicit-explicit attitude correspondence (Huntsinger & Smith, in press), and theory-of-mind usage (Converse, Lin, Keysar, & Epley, 2008), which demonstrate that people in positive moods utilize, and those in negative moods avoid, whatever cognitions and response tendencies that happen to be in mind the moment (for reviews, see Brinol & Petty, 2008; Clore & Huntsinger, in press).

If affect signals the value of any accessible mental content or response tendency, rather than solely triggering reliance on pre-existing general knowledge structures such as stereotypes, then the connection between affect and stereotyping should depend on the accessibility of stereotype-relevant thoughts and response tendencies. When thoughts and response tendencies that undermine, or directly counter, stereotype activation are most accessible, positive affect should actually lead to less stereotyping than negative affect—reversing the usual association between affect and stereotyping. When such thoughts and response tendencies are not accessible, as is often the case, positive affect should increase stereotyping, consistent with past research. According to this perspective, for example, positive mood should reduce stereotype activation among individuals for whom the goal to be egalitarian is chronically accessible, but should increase stereotype activation among individuals for whom this goal is not chronically accessible. Similarly, positive mood should reduce stereotype activation among individuals for whom counter-stereotypic exemplars are made accessible (e.g., strong female-leaders; Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004), but should increase stereotype activation among individuals for whom such exemplars are not currently salient.

Across four experiments, we tested whether the link between affect and stereotype activation hinges on the relative accessibility of stereotype-relevant thoughts and response tendencies. In the first two experiments, the relative accessibility of egalitarian versus non-egalitarian response tendencies was measured (Experiment 1) or manipulated (Experiment 2) and, in Experiments 3 - 4, counter-stereotypic thoughts were or were not made accessible. We manipulated mood using music and measured stereotype activation, the outcome of interest. With respect to measuring stereotype activation, Experiment 1 used a lexical decision task (see Moskowitz et al., 1999), Experiments 2 and 3 used the implicit association task (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwarz, 1998), and Experiment 4 used the weapon-identification task (Payne, 2001). We hypothesized that when thoughts and response tendencies that undermine stereotyping are accessible, positive mood would lead to less stereotype activation than negative mood. And, when such thoughts and response tendencies are not accessible, we expected positive mood to lead to greater stereotype activation than negative mood, mirroring the results of past research.

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we examined the effect of mood on stereotype activation among men for whom the goal of being egalitarian toward women was, or was not, chronically accessible. We hypothesized that positive mood should lead to decreased stereotype activation compared to negative mood for participants with a chronic goal to be egalitarian. In contrast, we hypothesized that for participants without a chronic goal to be egalitarian, the usual link between mood and stereotyping would be observed—increased stereotype activation among positive mood-participants compared to negative-mood participants.

Method

Participants

From a sample of 194 male undergraduates, we selected 16 men who held chronic egalitarian goals and 16 who did not, using a screening procedure validated and described in detail by Moskowitz et al. (1999). In brief, we identified chronic egalitarians by forcing men to endorse stereotypic explanations of women’s behavior and then observing whether these men exhibited compensatory behavior, as would be expected if they held strong, chronic egalitarian goals. Participants completed the main study in groups of one to four in exchange for course credit or payment.

Procedure

In the main experimental session, which took place least ten days after the preselection phase, participants were randomly assigned to spend ten minutes listening to either happy or sad music, thereby inducing positive or negative mood. Next, they completed a measure of gender stereotype activation, and finally they rated their moods as a manipulation check.

Materials

Stereotype activation measureWe assessed stereotype activation using a lexical decision task. On each trial, a male or female face appeared for 200 ms, followed immediately by a letter string. Participants were instructed to press one key if the letter string was a real word and a different key if it was a non-word. Participants were presented with 18 words related to the female stereotype (e.g., gentle, irrational), as well as 18 stereotype-irrelevant words (e.g., sleepy, colorful) and 36 non-words (for a total of 72 trials).

Following Wittenbrink, Judd and Park (1997), incorrect responses (3.9%) and latencies less than 150 ms and greater than 3,000 ms were deleted. Next response latencies were log-transformed to reduce skew. Finally, to create a measure of stereotype activation, for trials preceded by a female-face prime, we subtracted responses to stereotype-relevant female words from responses to stereotype-irrelevant female words. Higher numbers indicated greater female-stereotype activation. For ease of interpretation, raw response latencies are reported. Due to computer error, responses from two participants were lost.

Manipulation checksTo evaluate the efficacy of the mood manipulation, we asked participants to report how pleasant and gloomy (reverse-coded) they felt while listening to the music, 1 = not all to 7 = very. We averaged participants’ ratings of how pleasant they felt and how gloomy they felt (reverse-scored) to create a composite measure of positive mood.

Results

All hypotheses were evaluated via a 2 (mood: positive, negative) X 2 (egalitarian goal: yes, no) analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Manipulation Checks

The mood manipulation was successful. Participants in the positive-mood condition reported significantly more positive affect (M = 6.18; SD = 0.80) than participants in the negative-mood condition (M = 5.38; SD = 1.14), F (1, 27) = 5.01, p = .03, all other F’s < 1, p’s > .3.

Stereotype Activation

We hypothesized that the relative accessibility of a chronic motivation to be egalitarian would dictate whether positive or negative mood led to more or less stereotype activation. Specifically, we predicted that when the motivation to be egalitarian was present, participants in positive mood would exhibit less stereotype activation than those in negative moods. In contrast, in the absence of chronic motivation to be egalitarian, participants in positive moods would exhibit greater stereotype activation than those in negative moods.

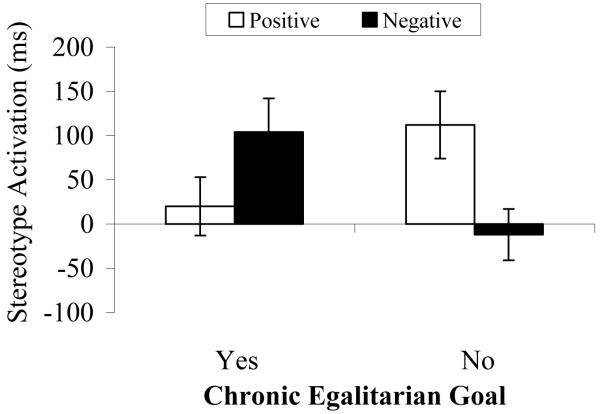

When we submitted the log-transformed measure of stereotype activation to the ANOVA described above, the only reliable effect to emerge was the predicted significant interaction between mood and egalitarianism, F (1, 26) = 8.05, p = .009, η2p = .24 (see Figure 1). For participants with a chronic goal to be egalitarian, positive mood tended to lead to decreased stereotype activation (M = 20.68, SD = 58.67) as compared to negative mood (M = 103.56, SD = 106.55), t (26) = 2.00, p = .076, d = .78. In contrast, for participants without a chronic goal to be egalitarian, positive mood led to increased stereotype activation (M = 112.22, SD = 120.87) relative to negative mood (M = −12.18, SD = 92.10), t (26) = 2.20, p < .05, d = .86.

Stereotype activation (in milliseconds) as function of presence of chronic egalitarian goal and mood. Note higher numbers indicate greater stereotype activation (i.e., speed).

Discussion

As hypothesized, the presence or absence of a chronic goal to be egalitarian dictated whether positive mood increased or decreased gender-stereotype activation relative to negative mood. For participants motivated by a chronic goal to be egalitarian experiencing a positive mood exhibited less gender-stereotype activation than those in a negative mood. In contrast, for participants not motivated by a chronic goal to be egalitarian, positive mood led to increased stereotype activation compared to negative mood, conceptually replicating past research (e.g., Bless et al., 1996; Bodenhausen et al., 1994; Isbell, 2004).

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 focused on the influence of mood and momentarily (rather than chronically) accessible egalitarian response tendencies on stereotype activation. Past research demonstrates that motivations and goals can be triggered by exposure to goal-relevant stimuli in the environment (Bargh, Gollwitzer, Lee-Chai, Barndollar, & Troetschel, 2001; Moskowitz, Li, & Kirk, 2004). Thus, in Experiment 2, we manipulated mood and exposed participants to words related or unrelated to egalitarianism (thereby making egalitarian goals accessible or not). The outcome of interest was the degree of stereotype activation exhibited by participants, in this case an association between male + leader and female + supporter, as measured by the implicit association task (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwarz, 1998). We hypothesized that when an egalitarian goal was temporarily accessible, positive mood would lead to decreased stereotype activation compared to negative mood, whereas positive mood would lead to increased stereotype activation in the absence of an accessible egalitarian goal.

Method

Participants

Forty participants (33 women) took part in this experiment for partial fulfillment of a course requirement.

Procedure

An experimenter greeted participants outside of the experiment room. Participants were then led into the room and seated in front of a computer. Next, participants read and signed an informed consent agreement. The experimenter then told participants that during the experiment they would complete a series of computer-based measures and answer some questions about their social attitudes. As in Experiment 1, prior to beginning the main part of the experiment, participants were told that we were pre-testing a series of musical selections for use in another experiment (thereby masking the true purpose of the mood induction). All participants agreed to take part in the pre-testing and were randomly assigned to either the positive or the negative mood induction used in Experiment 1.

The experimenter then started the computer program that would guide them through the rest of the experiment, told participants to come get him or her when the computer-based tasks were complete, and left the room. Instructions on the computer told participants to put on a pair of headphones, press a series of computer keys to start the musical selection, and adjust the volume to a desirable level. Participants listened to the music for approximately four minutes before the screen advanced to the next stage of the experiment. Participants next completed a lexical decision task as the music continued to play. However, unbeknownst to participants they were being subliminally primed with either words related to egalitarianism or neutral words.

After the lexical decision task, participants completed the measure of stereotype activation and answered a series of questions assessing the effectiveness of the mood manipulation, as well as some demographic items. After this, the experimenter thoroughly debriefed participants via a funneled debriefing procedure (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000). During the funneled debriefing, no participants expressed awareness of the true purpose of either the category priming manipulation or the mood induction.

Materials

Priming procedureA lexical decision task was used to subliminally prime participants with either words related or unrelated to egalitarianism. During this task, participants were instructed to respond with the “5” key if the stimulus was a word or the “a” key if the stimulus was a non-word. Prior to each word or non-word appearing on the screen, participants were exposed to either a word related to egalitarianism (e.g., egalitarian, fair, equality) or an unrelated word (e.g., chair, desk, television) for 40 milliseconds; the target words that participants consciously viewed were always unrelated to egalitarianism. A mask (e.g., XXXXXXX) preceded and followed presentation of each prime word. The forward and backward masks remained on the screen for approximately 150 and 15 milliseconds, respectively. They were included to minimize the chance that participants would be able to consciously recognize the prime words. Results of a funneled debriefing revealed that no participants reported seeing the prime words. Thus, the forward and backward masks served their purpose. The entire task consisted of 10 practice and 60 test trials and all stimuli appeared in the center of the computer screen. Words or non-words remained on the screen until participants provided the correct answer. Incorrect answers elicited a red error message in the middle of the screen. A total of ten words represented each category.

Stereotype activationAn implicit association task (IAT) was used to measure stereotype activation. Specifically, this measure was designed to assess the extent to which participants associated men + leader and female + supporter versus men + supporter and female + leader and was modeled after previous research (see Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004, for complete details). Response latencies were dealt with following the recommendations of Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003) and all reported analyses used the D-600 measure as the measure of implicit stereotyping because an error penalty was not built into the IAT for incorrect responses. Higher values on this measure indicate greater stereotype activation (i.e., a greater activation of an association of men + leader and female + supporter than the reverse).

Mood manipulation checkWe assessed the efficacy of the mood manipulation by asking participants to rate how positive, negative, happy, and sad they had felt while listening to music on seven-point scales (1 = not all to 7 = very much); after appropriate rescoring, a composite measure was formed, such that higher numbers indicated more positive mood (α = .90).

Results

All predictions were examined via a 2 (mood: positive, negative) X 2 (prime: egalitarian, neutral) ANOVA.

Mood manipulation check

The mood induction was successful. Participants felt more positive during the positive-mood induction (M = 5.67, SD = .90) than the negative-mood induction (M = 4.48, SD = 1.34), F (1, 36) = 10.72, p = .002, η2p = .23, all other F’s < 1, p’s > .5.

Stereotype activation

We hypothesized that participants’ mood and the relative accessibility of egalitarian goals would work in concert to shape stereotype activation. Specifically, we predicted that when an egalitarian goal was made accessible, positive mood would empower this response, leading to less stereotype activation compared to negative mood. In contrast, we predicted that when an egalitarian goal was not made accessible, positive mood would lead to greater stereotype activation compared to negative mood.

When the measure of stereotype activation was submitted to the ANOVA described above, the only reliable effect to emerge from these analyses was the predicted interaction, F (1, 36) = 11.52, p < .002, η2p = .24 (see Figure 2). As predicted, when an egalitarian goal was made accessible, participants in positive moods displayed less stereotype activation (M = .16, SD = .27) than those in negative moods (M = .51, SD = .19), t (36) = 3.11, p = .003, d = 1.04. When an egalitarian goal was not accessible, however, participants in positive moods exhibited somewhat greater stereotype activation (M = .40, SD = .33) than those in negative moods (M = .23, SD = .20), t (36) = 1.63, p = .11, d = .54, consistent with previous research.

Gender-stereotype activation (IAT-D score) as a function of prime (egalitarian versus control) and mood. Note: error bars represent standard errors.

Experiment 3

In a third experiment, we moved our focus from chronic and temporary egalitarian goals to the relative accessibility of counter-stereotypic thoughts to provide converging evidence that the link between affect and stereotyping depends, critically, on the accessibility of stereotype-relevant thoughts and responses. To accomplish this, positive and negative mood participants were exposed to a series of either strong female leaders or flowers to make accessible counter-stereotypic or neutral thoughts, respectively. Participants’ degree of stereotype activation was then measured. Previous research (e.g., Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004) found that participants exhibited less stereotype activation when exposed to strong female leaders than when exposed to the neutral category flowers. Based on the idea that affect confers value on any accessible thoughts and response tendencies (e.g., Clore & Huntsinger, in press), we predicted that when counter-stereotypic thoughts were most accessible, people in positive moods would display less stereotype activation than those in negative moods. In contrast, we predicted that when such thoughts were not accessible, people in positive moods would display greater stereotype activation than those in negative moods.

We also examined another account of affective regulation of stereotype activation, namely, possible arousal differences between the positive and negative mood inductions. It is possible, for example, that the positive mood induction increased arousal compared to the negative mood induction, which could have led participants in positive moods to utilize, and those in negative moods to reject, accessible thoughts and response tendencies (Bargh & Cohen, 1978; Zajonc, 1965). It is important to note that the existing evidence supporting an arousal-based explanation for affective regulation of stereotyping is mixed best. Bodenhausen and colleagues (1994), for instance, found that positive mood increased stereotyping, regardless of whether the mood was associated with high or low levels of arousal. Nevertheless, following past research (Huntsinger & Smith, in press; Tamir, Robinson, & Clore, 2002), to address this possibility, we measured participants’ self-reported arousal by asking them how alert (tired) they felt during the mood induction.

Method

Participants

Thirty-nine participants (24 women) took part in the experiment to partially fulfill a course requirement.

Procedure

The procedure for this experiment was similar to that of Experiment 2, but instead of priming egalitarian concepts using a lexical decision task, we showed participants photos and descriptions of strong female leaders to prime counter-stereotypic thoughts (while control participants viewed pictures of flowers). All other procedural details of this experiment (including the stereotype activation measure and mood manipulation checks) were identical to Experiment 2.

Materials

Thoughts manipulationThe manipulation of counter-stereotypic versus neutral thoughts was based on previous research (e.g., Dasgupta & Asgari, 2004). To make counter-stereotypic thoughts accessible, participants viewed sixteen photos of past and present well-known female leaders (i.e., Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Gloria Steinem, etc.). Each photo was accompanied by a brief paragraph describing each woman’s accomplishments. In the neutral thoughts condition, participants viewed sixteen photos of flowers (i.e., rose, tulip, etc.). Each photo was accompanied by a brief paragraph describing the flower’s appearance, growing habits, region of origin, and other features of the flower.

At the beginning of this task, instructions on the computer screen informed participants the photos and descriptions they were about to view were being pre-tested for another experiment that would take place next semester. Participants then viewed sixteen photos and brief descriptions of strong female-leaders or flowers and navigated the task their own pace by pressing the space bar to advance the screen to the next female leader (or flower). However, they could not go backwards. The order of the sixteen photos and descriptions was randomized within each priming condition. Suggesting that the thoughts manipulation was equally successful across conditions, the average time participants spent reading the slides did not differ as a function of induced mood, thought accessibility condition, or the interaction between the two, all Fs < 1.0, ps >.7. Finally, a funneled debriefing revealed that no participants expressed awareness of the true purpose of this task.

Stereotype activationThis measure was administered and scored as in Experiment 2.

Mood manipulation checkAs in Experiment 2, participants’ four mood ratings were used to create a composite measure of positive mood (α = .90). One participant’s responses were lost due to computer error.

ArousalTo determine whether the positive and negative mood inductions elicited different levels of arousal, participants were asked to rate how alert and tired they felt while listening to the music on a seven-point scales (1 = not all to 7 = very much).. After appropriate rescoring, a composite measure was formed, such that higher numbers indicated greater arousal (r = .74). One participant’s response to this measure was lost due to computer error.

Results

All predictions were examined via a 2 (mood: positive, negative) X 2 (prime: female-leader, flowers) ANOVA.

Mood Manipulation Check

The mood induction was successful. Participants felt more positive during the positive-mood induction (M = 5.99, SD = .80) than the negative-mood induction (M = 5.25, SD = 1.08), F (1, 34) = 6.14, p = .018, η2p = .15. No other effects were significant, F’s < 1.8, all p’s > .2.

Stereotype activation

We predicted that the influence of affect on stereotype activation would depend on the relative accessibility of counter-stereotypic thoughts. When counter-stereotypic thoughts were made accessible, positive mood was expected to lead to less stereotype activation compared to negative mood. When counter-stereotypic thoughts were not made accessible, positive mood would was expected to lead to greater stereotype activation compared to negative mood.

Only the predicted interaction between prime and mood was significant, F (1, 35) = 8.79, p = .005, η2p = .20 (see Figure 3). Consistent with predictions, participants exposed to strong female-leaders exhibited less stereotype activation if they were in a positive (M = .35, SD = .28) versus negative (M = .64 SD = .34) mood, t (35) = 2.09, p = .045, d = .71. In contrast, participants exposed to flowers displayed greater stereotype activation if they were in a positive (M = .62, SD = .30) versus negative (M = .32, SD = .29) mood, t (35) = 2.12, p = .042, d = .72.

Gender-stereotype activation (IAT-D score) as a function of exemplar exposure (strong female-leader versus flowers) and mood. Note: error bars represent standard errors.

Arousal

Inconsistent with an arousal-based account, participants reported feeling similar levels of arousal while listening to the positive (M = 4.31, SD = 1.50) and negative (M = 4.15, SD = 1.40)music, F (1, 34) = .12, p = .73, η2p = .04. No other effects were significant, F’s < 1.3, all p’s > .25.

Experiment 4

The results of Experiments 1-3 provided strong evidence consistent with the idea that whether positive mood enhances gender-stereotype activation relative to negative mood depends critically on the relative accessibility of counter-stereotypic thoughts and response tendencies. When thoughts and response tendencies that undermine stereotyping are most accessible, then positive mood leads to lesser stereotype activation than negative mood, reversing the usual link between mood and stereotype activation. By contrast, when such thoughts and response tendencies are not accessible, then positive mood leads to greater stereotype activation than negative mood, consistent with past research.

Despite the consistency of results across Experiments 1-3, we thought it important to demonstrate that this pattern holds for activation of stereotypes other than those related to gender. Accordingly, in Experiment 4, we examined activation of race-related stereotypes in the weapon-identification task (Payne, 2001). In this task, participants determine whether a presented object is a weapon or a tool. Preceding the presentation of a weapon or tool, participants are briefly exposed to either a Black or White face. In the weapon-identification task, and similar paradigms, participants are more likely to mistakenly categorize a tool as a weapon if it follows exposure to a Black face than a White face and to categorize a weapon as a tool if it follows exposure to a White face than a Black face (Correll, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2002; Greenwald, Oakes, & Hoffman, 2003; Payne, 2001). This pattern of errors is generally taken to indicate activation of a stereotype associating African Americans and criminality or danger.

Further, more direct, evidence of stereotype activation on the weapon identification task comes from application of process-dissociation procedures designed to parse individuals’ responses in this task into the product of controlled and automatic processing (Jacoby, 1991; Payne, 2001). Fundamental to the process-dissociation procedure (PDP) is the idea that controlled and automatic processes are independent, and can concurrently contribute to behavior on a given task. To determine the relative contribution of controlled and automatic processing to responses obtained within this task one compares performance on stereotype congruent (i.e., Black face/weapon; White face/tool) versus incongruent (i.e., Black face/tool; White face/weapon) trials. In congruent trials, accurate identification of a weapon or tool could result from controlled processing (i.e., efforts to constrain processing to task-relevant information) or automatic processing (i.e., automatic stereotype activation; Payne, 2005). In congruent trials, for example, both controlled efforts to execute the correct response to the presented object and automatically activated stereotypes linking African Americans with criminality/danger could lead to a correct response when presented with a weapon. In incongruent trials, however, these controlled and automatic processes are in conflict with one another. On the one hand, controlled processing should facilitate correct responding (e.g., respond tool when presented with a tool). On the other hand, the influence of automatic stereotype activation (e.g., an association between African Americans and crime/danger) should facilitate errors (e.g., respond weapon when presented with a tool).

Given these conditions, the PDP can estimate the contribution of controlled and automatic processing to behavior in the weapon-identification task (Payne, 2001). Specifically, on congruent trials, correct responses could be driven by either controlled processing (C) or automatic processing (A) given a failure of control (1 −C). This can be expressed by the following equation:

P(correct∣congruent) = C + A(1 − C)

(1)

On incongruent trials, these two processes are opposed to one another. If control fails, automatic processing (i.e., activated stereotypes) drives participants’ responses, leading to incorrect responses. This can be expressed by the following equation:

P(error∣incongruent) = A(1 − C)

(2)

Based on these two equations, one can algebraically solve for estimates of controlled and automatic processing:

C = P(correct∣congruent) − P(error∣incongruent)

(3)

A = P(error∣incongruent) ∕ (1 − C)

(4)

Existing research has successfully estimated the role of controlled and automatic processes in the weapon-identification task, established that the PDP controlled estimate reflects controlled efforts to constrain processing to task demands or goal-relevant information and the PDP automatic estimate represents the degree of automatic stereotype activation (for a review, see Payne & Stewart, 2007).

Automatic stereotype activation on the weapon-identification task initially appeared quite resistant to change (for a review, see Payne & Stewart, 2007). Explicitly instructing participants to avoid stereotypical bias on the weapon identification task, for example, ironically increases stereotypical mistakes and, as revealed by process-dissociation analysis, this is driven by increases in stereotype activation and not increased controlled processing (Payne, Lambert, & Jacoby, 2002). Recent research, however, demonstrated that making accessible counter-stereotypic thoughts and response tendencies by means of implementation intentions (Gollwitzer, 1999) reduced stereotype activation (Stewart & Payne, 2008). Specifically, in this research participants instructed to think “safe” in response to Black faces exhibited few stereotypical mistakes in the weapon-identification task compared to those instructed to think “quick” or to think “accurate” in response to Black faces, who displayed the usual pattern of stereotypical mistakes. Process-dissociation procedures revealed that this reduction in stereotypical mistakes was driven by change in stereotype activation and not increased controlled processing on the part of participants to offset the impact of activated stereotypes on their responses (Stewart & Payne, 2008).

In summary, in Experiment 4, we moved our focus to the influence of mood and momentarily accessible counter-stereotypic thoughts on race-related stereotype activation in the weapon identification task. Participants’ mood was manipulated via music as in Experiments 1-3, counter-stereotypic thoughts were made accessible (i.e., think “safe” condition) or not (i.e., think “accurate” condition) via Stewart and Payne’s (2008) think “accurate/safe” task and, finally, participants completed the weapon-identification task. We predicted that when instructed to think “safe,” participants in positive moods would display fewer stereotypical mistakes on the weapon-identification task than those in negative moods. By contrast, when instructed to think “accurate,” we predicted that participants in positive moods would exhibit more stereotypical mistakes than those in negative moods. Based on prior research (e.g., Stewart & Payne, 2008) we expected variation in stereotypical mistakes across conditions to be driven by change in stereotype activation and not change in controlled processing, a prediction we investigated via process-dissociation analyses.

Method

Participants

Eighty-one (50 women) participants completed this experiment for partial fulfillment of a course requirement.

Procedure

The procedure for this experiment was similar to that of Experiments 1-3. Once participants arrived, they were seated in front of a computer, signed an informed consent agreement, and were told they would complete a series of computer-based measures and then complete a brief questionnaire. Participants were then told we were pre-testing a series of musical selections for another, unrelated experiment. All participants agreed to take part in the pre-testing and were randomly assigned to one of two mood inductions used in Experiments 1-3. Following the mood induction, which lasted approximately 12 minutes, participants completed a practice version of the weapon-identification task, the thoughts manipulation, the critical version of the weapon-identification task, a mood manipulation check, and some demographic items. Finally, participants were thoroughly debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Materials

Weapon-identification taskThe weapon-identification task used in this experiment was identical to Payne’s (2001) Experiment 1. Participants were informed that the task measured speed and accuracy and that they would see two pictures briefly presented on the computer screen. They were told to ignore the first picture, a face, and only respond to the second picture by indicating whether it was a gun or tool using one of two computer keys. Participants were told to respond as quickly and accurately as possible and if they made a mistake to continue to the next trial.

In both practice (24 trials) and test trials (128 trials), participants were first exposed to a prime (a White or Black face) and then a target (a tool or gun). The prime remained on the screen for 200 ms and was immediately replaced by the target. The target remained on the screen for 200 ms and was then replaced by a visual mask, which remained on the screen until participants responded. After completing the practice trials, participants experienced the thoughts manipulation task described below and then completed the test trials.

Thought Manipulation TaskIn the thought manipulation task, virtually identical to Stewart and Payne (2008), participants were first informed that the race of the primes influences how they classify the second object. They then read a few sentences describing how making a resolution to respond in a certain way can change one’s reactions. After reading this passage, participants were then randomly assigned to either the counter-stereotypic condition or the accuracy condition.

In the counter-stereotypic condition, participants read the following instructions (Stewart & Payne, 2008; page 1334):

“We would like you to commit yourself to responding to the Black face by thinking the word ‘safe.’ By thinking the word ‘safe,’ you are reminding yourself on each trial that you are just as safe interacting with a Black individual as with a White individual. In order to firmly commit yourself to responding to the Black face, please say to yourself silently, ‘I definitely want to respond as accurately as possible by thinking the word, safe. Whenever I see a Black face on the screen, I will think the word, safe.’”

In the accuracy condition, which mirrors the weapon-identification task instructions, participants read the following instructions (Stewart & Payne, 2008; page 1334):

“We would like you to commit yourself to responding to the Black face by thinking the word ‘accurate.’ By thinking the word ‘accurate,’ you are reminding yourself on each trial that you should accurately identify the objects that appear after the Black and White faces. In order to firmly commit yourself to responding to the Black face, please say to yourself silently, ‘I definitely want to respond as accurately as possible by thinking the word, accurate. Whenever I see a Black face on the screen, I will think the word, accurate.’”

Immediately after reading these instructions, participants in both conditions completed the weapon-identification test trials.

Mood-manipulation checkParticipants were asked six questions to determine the efficacy of the mood induction (e.g., How positive [negative, happy, sad, good, bad] did you feel while you listened to the musical selection; 1 = not all to 7 = very much). After appropriate recoding, a composite measure of positive mood was formed (α = .89). One participant failed to complete these items.

Results

Mood-manipulation check

The mood manipulation was successful. Participants felt more positive during the positive-mood induction (M = 6.05, SD = .78) than the negative-mood induction (M = 5.25, SD = 1.05), F (1, 76) = 14.79, p < .0005, η2p = .16.

Error rates

We submitted the error rate data to a 2 (mood: positive, negative) X 2 (thought: safe, accurate) X 2 (prime: black, white) X 2 (target: weapon, tool) mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the last two factors varying within participants. This analysis revealed the predicted four-way interaction, F (1, 77) = 31.54, p < .0005, η2p = .29 (see Figure 4).

Race-relevant stereotype activation (i.e., proportion of errors) as a function of prime (Black face vs. White face), Target (weapon vs. tool), Thought condition (safe vs. accuracy), and mood (positive vs. negative). Note: error bars represent standard errors.

Consistent with predictions, in the safe condition participants in positive moods displayed fewer stereotypical mistakes than those in negative moods. Specifically, safe-condition participants in positive moods were no more likely to misidentify a tool as a gun after being primed with a Black face than a White face, t (77) = .30, p = .76, d = .07, and less likely to misidentify a gun as a tool after being primed with a White face versus a Black face, t (77) = 2.08, p = .04, d = .47. Safe-condition participants in negative moods, by contrast, exhibited a stereotypic pattern of errors —they were more likely to misidentify a tool as a gun after being primed with a Black face than a White face, t (77) = 2.00, p = .042, d = .46, and more likely to misidentify a gun as a tool after being primed with a White face than a Black face, t (77) = 2.08, p = .034, d = .47.

Also consistent with predictions, in the accuracy condition participants in positive moods displayed more stereotypical mistakes than those in negative moods. Specifically, consistent with stereotypes, accuracy-condition participants in positive moods were more likely to misidentify a tool as a gun after being primed with a Black face than a White face, t (77) = 3.90, p < .0005, d = .89, and more likely to misidentify a gun as a tool after being primed with a White face than a Black face, t (77) = 2.41, p = .023, d = .55. In contrast, accuracy-condition participants in negative moods did not display a stereotypic pattern of tool, t (77) = .64, p = .53, d = .15, or gun, t (77) = 1.36, p = .18, d = .31 misidentifications.

PDP analyses

Estimates of controlled and automatic processing on the weapon identification task were created using Equations 1-4 described earlier. Following Payne (2001), for the Black prime conditions, the controlled estimate was created by subtracting the probability of incorrect responses when tool was primed with a Black face from the probability of correct responses when gun was primed with a Black face. The automatic estimate was then derived by taking the probability of incorrect responses when tool was primed with a Black face and dividing it by (1 - C). Estimates of controlled and automatic processing for the White prime conditions were calculated via the same method. Higher values on the two controlled estimates represented a greater tendency to exert cognitive control upon presentation of White or Black primes. Higher values on the two automatic estimates represented a greater automatic tendency to respond gun in the presence of a White or Black prime.

We submitted the PDP controlled and automatic estimates to separate 2 (mood: positive, negative) X 2 (thought: safe, accurate) X 2 (prime: black, white) mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with the last factor varying within participants. These analyses revealed that the above pattern of change in error rates was indeed due change in stereotype activation and not change in controlled processing. Specifically, there was a significant interaction for automatic estimates, F (1, 77) = 34.39, p < .0005, η2p = .31 (see Figure 5). Controlled estimates did not vary as a function of mood and/or thought, all ps > .22.

Automatic race-stereotype activation (i.e., PDP automatic estimate) as a function of prime (Black face vs. White face), Thought condition (safe vs. accuracy), and mood (positive vs. negative). Note: error bars represent standard errors.

In the safe condition, participants in positive moods displayed less stereotype activation than those in negative moods. Specifically, positive-mood participants in this condition displayed a greater stereotype-inconsistent tendency to respond gun after presentation of White primes than Black primes, t (77) = 2.15, p = .033, d = .49. Negative-mood participants, by contrast, displayed a greater stereotype-consistent automatic tendency to respond gun after presentation of Black primes than White primes, t (77) = 2.40, p = .04, d = .55.

In the accuracy condition, the opposite pattern of stereotype activation was found—participants in positive moods displayed greater stereotype activation than those in negative moods. Specifically, positive-mood participants displayed a greater stereotype-consistent automatic tendency to respond gun after presentation of Black primes than White primes, t (77) = 5.43, p < .0005, d = 1.24. In contrast, negative-mood participants in this condition displayed a somewhat greater stereotype-inconsistent tendency to respond gun after presentation of White primes than Black primes, t (77) = 1.84, p = .07, d = .42.

In summary, whether positive or negative mood participants committed a pattern of errors on the weapon-identification task reflecting a stereotypical bias depended, critically, on whether accessible thoughts undermined stereotype activation. Specifically, when instructed to think “safe,” participants in positive moods exhibited fewer stereotypical mistakes than those in negative moods. By contrast, when instructed to think “accurate,” participants in positive moods displayed more stereotypical mistakes than those in negative moods. Process-dissociation analysis confirmed that this variation in stereotyping was indeed driven by change in stereotype activation rather than change in controlled processing (Stewart & Payne, 2008).

General Discussion

The results of four experiments revealed that the link between affect and stereotyping hinges on the relative accessibility of stereotype-relevant thoughts and response tendencies. When thoughts and response tendencies that undermine stereotyping are most accessible, the usual link between affect and stereotyping reverses—positive affect now leads to less stereotype activation than negative affect. In contrast, when such thoughts and response tendencies are not accessible—as is often the case—then positive affect leads to greater stereotype activation than negative affect. Underscoring the robustness of this effect, this pattern was found across four experiments that employed four different measures or manipulations of accessible thoughts and response tendencies, three different measures of stereotype activation, and activation of both gender and race stereotypes.

The present research advances our understanding of how affect regulates stereotyping in several important ways. By changing people’s most accessible stereotype-relevant thoughts and response tendencies, we were able to disrupt what is thought of as the usual link between positive affect and stereotyping found in prior work (e.g., Bless et al., 1996; Bodenhausen et al., 1994; Krauth-Gruber & Ric, 2000; Park & Banaji, 2000; for reviews see Bodenhausen et al., 2001; Schwarz & Clore, 2007). Our findings suggest that instead of a direct link between affect and reliance on general knowledge structures such as stereotypes, the relationship between affect and stereotyping may reflect a more general manner by which affect regulates cognitive processing—positive and negative affect confer positive or negative value on whatever thoughts and inclinations are most accessible in the mind the time. Further support for the idea that affect confers value on whatever cognitions and response tendencies are in mind the time comes from research examining the influence of affect on self-validation processes (e.g., Brinol et al., 2007), goal pursuit (Fishbach & Labroo, 2007; Huntsinger & Sinclair, 2008), implicit-explicit attitude correspondence (Huntsinger & Smith, in press), and theory-of-mind use (Converse et al., 2008), which all show that people in positive moods tend to embrace, and those in negative moods avoid, whatever thoughts and other mental content that happen to be in mind the time (for reviews, see Brinol & Petty, 2008; Clore & Huntsinger, in press). This is not meant to imply, however, that we discovered the exclusive manner by which affect regulates cognitive processing. As previous research amply demonstrates (e.g., Hirt, Levine, McDonald, Melton, & Martin, 1997; Wegener and Petty, 2001), affect may influence cognition in a variety of ways—even within the same experimental context. Future research is essential to delineate when affect regulates cognitive processing by signaling the value of accessible mental content and when affect exerts its influence in other ways.

Additionally, the present research examined affective regulation of stereotype activation, unlike the majority of past research, which focused on the impact of stereotypes on more controlled judgments (for a review, see Bodenhausen, Mussweiler, Gabriel, & Moreno, 2001). From past research it is unclear whether affect regulated the activation of stereotypes, or whether it regulated the application of stereotypes when making judgments. The current research, perhaps most convincingly the process-dissociation analyses from Experiment 4, suggests that mood does indeed regulate the activation of stereotypes and other mental content (see also Huntsinger, Sinclair, & Clore, 2008; Storbeck & Clore, 2008).

Coda

In closing, the present research demonstrates that the link between affect and stereotyping is quite malleable and hinges on the relative accessibility of counter-stereotypic thoughts and response tendencies. When thoughts and response tendencies that undermine stereotyping are accessible—whether because of a chronic or temporary motivation to be egalitarian or exposure to counter-stereotypic exemplars and thoughts—positive affect leads to reduced stereotype activation compared to negative affect. If, however, such thoughts and response tendencies are not accessible, as is often the case, then positive affect leads to greater stereotyping than negative affect.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were conducted as part of the first author’s dissertation. We acknowledge support from NIH grant K01 MH069419 to the second author, SSHRC grant 410-2005-0843 to the third author, and NIMH grant MH-50074 to the fourth author.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey R. Huntsinger, Loyola University Chicago.

Stacey Sinclair, Princeton University.

Elizabeth Dunn, University of British Columbia.

Gerald L. Clore, University of Virginia.

References

- Ashton-James C, Huntsinger J, Clore G. Affective Regulation of Social Category Priming: Attitude and Behavior. Unpublished Manuscript.

[Google Scholar]Banaji, Hardin Automatic Stereotyping.

Psychological Science. 1996;7:136–141. [Google Scholar]Bargh . The cognitive monster: The case against the controllability of automatic stereotype effects. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y, editors. Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology. Guilford; Tp New York: 1999.

[Google Scholar]Bargh JA, Chartrand TL. The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In: Reis

HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Cambridge University Press; Tp New York: 2000.

[Google Scholar]Bargh JA, Cohen JL. Mediating factors in the arousal-performance

relationship. Motivation and Emotion. 1978;2:243–257.

[Google Scholar]Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM,

Chai AL, Barndollar K, Troetschel R. Automated will: Nonconscious activation and pursuit of behavioral goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1014–1027. [PMC free article]

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Blair IV. The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:242–261.

[Google Scholar]Blair IV, Banaji M.

Automatic and controlled processes in stereotype priming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1142–1163.

[Google Scholar]Blair

IV, Ma JE, Lenton AP. Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of automatic stereotypes through mental imagery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:828–841. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Bless H. The relation between mood and the use of general knowledge structures. In: Martin LL, Clore GL, editors. Mood and social cognition: Contrasting theories. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 9–29.

[Google Scholar]Bless H, Clore G, Schwarz N, Golisano V, Rabe C, Wolk M. Mood and the use of scripts: Does happy mood

really lead to mindlessness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:665–679. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Bless H, Fiedler K. Mood and the regulation of information processing and behavior. In: Forgas JP, Williams KD, van Hippel W, editors. Hearts and minds: Affective influences on social cognition and behavior. Psychology Press; NE York: 2006.

pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]Bless H, Schwarz N, Kemmelmeier M. Mood and

stereotyping: The impact of moods on the use of general knowledge structures. European Review of Social Psychology. 1996;7:63–93.

[Google

Scholar]Bodenhausen G, Kramer G, Susser K. Happiness and stereotypic thinking in social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:621–632.

[Google Scholar]Bodenhausen GV, Mussweiler T, Gabriel S, Moreno KN. Affective influences on stereotyping and intergroup relations. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 319–343.

[Google Scholar]Briñol P, Petty RE. Embodied persuasion: Fundamental

processes by which bodily responses can impact attitudes. In: Semin GR, Smith ER, editors. Embodiment grounding: Social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscientific approaches. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2008. pp. 184–207.

[Google Scholar]Briñol P, Petty RE, Barden J. Happiness versus

sadness as a determinant of thought confidence in persuasion: A self-validation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:711–727. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Bruner J. On perceptual readiness. Psychological Review. 1957;64:123–152.

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Clore GL, Huntsinger J. How emotion informs judgments and

regulates thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;9:393–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Clore

GL, Huntsinger J. How the object of affect guides its impact. Emotion Review. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Clore GL, Wyer RS, Dienes B, Gasper K, Gohm CL, Isbell L. Affective Feelings as

Feedback: Some Cognitive Consequences. In: Martin LL, Clore GL, editors. Theories of mood and cognition: A user’s handbook. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 27–62.

[Google Scholar]Converse BA, Lin S, Keysar B,

Epley N. In the mood to get over yourself: Mood affects theory-of-mind use. Emotion. 2008;8:725–730. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Correll J, Park B, Judd CM, Wittenbrink B. The police officer’s dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1314–1329. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Corson Y, Verrier N. Emotions and false memories: Valence or arousal? Psychological Science. 2007;18:208–211.

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Dasgupta N, Asgari

S. Seeing is believing: Exposure to counterstereotypic women leaders and its effect on automatic gender stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40:642–658.

[Google Scholar]Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:817–830.

[Google Scholar]Devine

PG, Plant AE, Amodio DM, Harmon-Jones E, Vance SL. The regulation of implicit race bias: The role of motivations to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:835–848. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Ellis HC, Ashbrook PW. Resource allocation model of the effects of depressed mood states on memory. In: Fiedler K, Forgas J, editors. Affect, cognition and social behaviour. Hogrefe; Toronto: 1988.

[Google Scholar]Fishbach A, Labroo AA. Be Better or Be Merry: How Mood Affects Self-Control.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:158–173. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:493–503.

[Google Scholar]Greenwald A, Banaji M. Implicit

social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1995;102:4–27. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Greenwald

AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JKL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: I. An Improved Scoring Algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:197–216.

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Greenwald AG, Oakes MA, Hoffman H. Targets of Discrimination: Effects of Race on Responses to Weapons Holders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:399–405.

[Google

Scholar]Hense R, Penner L, Nelson D. Implicit Memory for Age Stereotypes. Social Cognition. 1995;13:399–415.

[Google Scholar]Hirt ER, Levine GM, McDonald HE,

Melton RJ, Martin LL. The role of mood in quantitative and qualitative aspects of performance: Single or multiple mechanisms? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1997;33:602–629.

[Google Scholar]Huntsinger J, Sinclair S. If it feels right, go with it: Affective regulation of affiliative social tuning. 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication.

[Google Scholar]Huntsinger J, Sinclair S, Clore GL.

Affective regulation of implicitly measured stereotypes and attitudes: Automatic and controlled processes. 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication.

[Google Scholar]Huntsinger

J, Smith CT. First thought, best thought: Positive mood maintains and negative mood disrupts implicit-explicit attitude correspondence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. in press. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]

Isbell L. Not all happy people are lazy or stupid: Evidence of systematic processing in happy moods. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40:341–349.

[Google Scholar]Jacoby LL. A process dissociation framework: Separating automatic from intentional uses of memory. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30:513–541. [Google Scholar]Krauth-Gruber S, Ric F. Affect and stereotypic thinking: A test of the mood-and-general-knowledge model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1587–1597.

[Google

Scholar]Kunda Z, Spencer SJ. When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgment? A goal-based theory of stereotype activation and application. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:522–544. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Lambert AJ, Khan SR, Lickel BA, Fricke K. Mood and the correction of positive versus negative stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1002–1016.

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Lepore L, Brown R. Category and stereotype activation: Is prejudice inevitable? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(2):275–287.

[Google Scholar]Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:803–855. [PubMed]

[Google

Scholar]Mackie DM, Worth LT. Feeling good, but not thinking straight: The impact of positive mood on persuasion. In: Forgas J, editor. Emotion and social judgment. Pergamon; Oxford: 1991. pp. 201–220.

[Google Scholar]Macrae CN, Bodenhausen GV. Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annual Review

of Psychology. 2000;51:93–120. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Miller GA,

Galanter E, Pribram KH. Plans and the Structure of Behavior. Holt, Rinehart & Winston; Tp New York: 1960. [Google

Scholar]Moskowitz GB. Social cognition: Understanding self and others. Guilford Press; Tp New York: 2005.

[Google Scholar]Moskowitz GB, Gollwitzer PM, Wasel W, Schaal B. Preconscious control of stereotype activation

through chronic egalitarian goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:167–184.

[Google

Scholar]Moskowitz GB, Li P, Kirk ER. The implicit volition model: On the preconscious regulation of temporarily adopted goals. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 34. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2004. pp. 317–414. [Google Scholar]Niedenthal PM, Setterlund MB. Emotion congruence in perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:401–411.

[Google Scholar]Park J, Banaji M.

Mood and heuristics: The influence of happy and sad states on sensitivity and bias in stereotyping. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2000;78:1005–1023. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Payne BK. Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:181–192.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]Payne BK. Conceptualizing control in social cognition: How Executive Functioning Modulates the Expression of Automatic Stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:488–503. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Payne BK, Stewart BD. Automatic and controlled components of social cognition: A process dissociation approach. In: Bargh JA, editor. Social Psychology and the Unconscious: The Automaticity of Higher Mental Processes. Psychology Press; New

York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]Revelle W, Loftus D. The

implications of arousal effects for the study of affect and memory. In: Christianson SA, editor. Handbook of emotion and memory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. pp. 113–150.

[Google Scholar]Schwarz N. Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In:

Sorrentino RM, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. Vol. 2. Guilford Press; Tp New York: 1990. pp. 527–561.

[Google Scholar]Schwarz N, Clore GL. Feelings and Phenomenal Experiences. In: Higgins ET,

Kruglanski A, editors. Social Psychology. A Handbook of Basic Principles. 2nd Ed. Guilford Press; Tp New York: 2007. pp. 385–407.

[Google Scholar]Sinclair L, Kunda Z. Reactions to a Black professional: Motivated inhibition and

activation of conflicting stereotypes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1999;77:885–904. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Stewart BD, Payne BK. Bringing automatic stereotyping under control: Implementation intentions as efficient means of thought control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1332–1345. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Storbeck J, Clore GL. With sadness comes accuracy, with happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychological Science. 2005;16:785–791.

[PubMed]

[Google

Scholar]Storbeck J, Clore GL. The affective regulation of semantic and affective priming. Emotion. 2008;8:208–215. [PMC free article]

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Tamir M, Robinson MD,

Clore GL. The epistemic benefits of trait-consistent mood states: An analysis of extraversion and mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:663–677. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Wegener DT, Petty RE. Understanding effects of mood through the Elaboration Likelihood and Flexible Correction models. In: Martin LL, Clore GL, editors. Theories of mood and cognition: A user’s guidebook. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001.

pp. 177–210. [Google Scholar]Wittenbrink B, Judd CM, Park B. Evidence for racial prejudice

the implicit level and its relationship with questionnaire measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:262–274. [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]Zajonc RB. Social Facilitation. Science. 1965;149:269–274.

[PubMed]

[Google Scholar]

In what ways do stereotypes influence people's judgments?

Because stereotypes can powerfully influence people's perceptions toward a stereotyped group, perceivers may infer positive or negative stereotyped characteristics when they are actually not true, and such stereotyped perceptions may influence people's moral judgments (Tsukiura & Cabeza, 2011; Wright & Nichols, 2014).What are the factors that influence stereotypes?

Stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination often come from:. inequalities in society.. ideas learned about other people/groups from family members, friends and/or the truyền thông.. not spending a lot of time with people who are different from you in some way.. not being open to different ideas and ways of living..What is stereotyping Judgement?

Among the various components of person judgment is the pro- cess of stereotyping, whereby beliefs about a social group are used in judgments of the group or individual members of the group.How are stereotypes activated?

In an influential model of prejudice, Devine (1989) proposed that stereotypes become over-learned due to their societal prevalence, and are automatically activated upon encounters with individual members of stereotyped groups. Tải thêm tài liệu liên quan đến nội dung bài viết Whose judgments are least likely to be influenced by automatic stereotype activation?

Post a Comment